“They waved white flags. They surrendered. Then they were lined up against a wall and executed—one by one. On the night of May 22, 1948, in the Palestinian village of Tantura, Israeli forces killed over 200 unarmed men and buried them in mass graves beneath their own homes. For decades, the story was silenced—denied, erased, and buried. Seventy-seven years later, the soil still speaks. Tantura was not a battlefield. It was a massacre.”

[Watch full documentary on: https://www.tantura-film.com/]

On the night of May 22-23, 1948, just one week after the declaration of the State of Israel, the Palestinian coastal village of Tantura was attacked and occupied by units of the Israeli army's Alexandroni Brigade. Located approximately 35 kilometers south of Haifa, Tantura fell within the area assigned to the Jewish state by the UN General Assembly's partition resolution. With a population of around 1,500, Tantura would suffer a fate similar to more than 400 other Palestinian villages during the 1948 war: occupation, depopulation, destruction, and the seizure of all its lands by Israel. However, Tantura also endured the additional tragedy of a large-scale massacre of its inhabitants, an atrocity that would remain largely overlooked for decades.

The Tantura massacre was overshadowed at the time by the broader conflict between Israel and the regular armies of Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, and Syria, which had entered Palestine following Israel's declaration of statehood. The first written reference to the massacre appeared around 1950 when Haj Muhammad Nimr al-Khatib, a Muslim cleric who had been an active member of the Arab National Committee of Haifa, published a compendium titled "Min Athar al-Nakba" (Consequences of the Catastrophe) in Damascus. This work included eyewitness accounts from Palestinian refugees, including testimonies from Tantura survivors. Among these were accounts by Iqab al-Yahya, a village notable, and his son Marwan, who described "the methodical shooting and burial in a communal grave of some forty young men in Tantura village." Khatib also reported cases of Tantura female rape victims being treated in a Nablus hospital.

The massacre gained renewed attention in 1998 through the work of Israeli researcher Teddy Katz, whose master's thesis at Haifa University documented the events in detail. Katz's research, based on taped testimonies from both survivors and members of the Alexandroni Brigade, concluded that more than 200 Tantura villagers, mostly unarmed young men, had been shot after the village surrendered. When a summary of his findings was published in the Hebrew press in January 2000, it ignited controversy in Israel, culminating in a 1 million shekel libel suit brought against Katz by veterans of the Alexandroni Brigade. The subsequent trial and its implications were later analyzed by Israeli historian Ilan Pappé, who also examined the broader historical context and significance of these events.

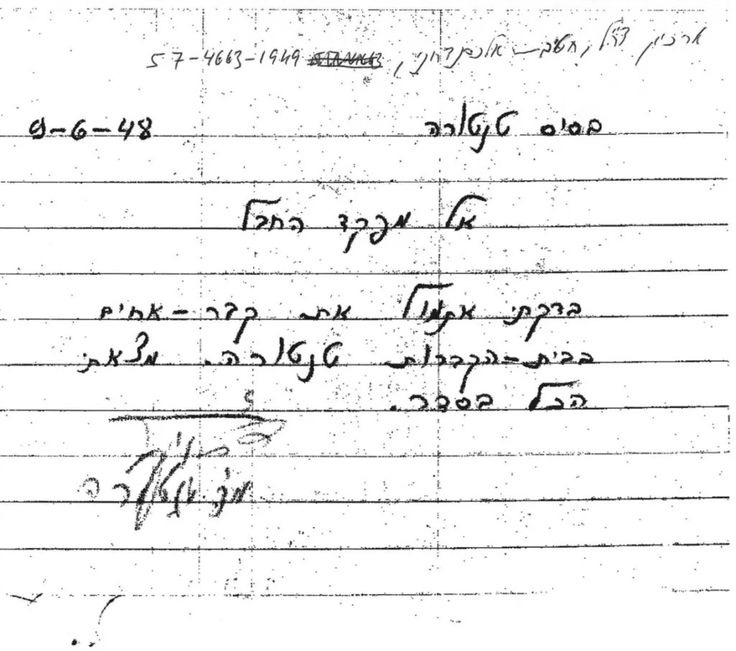

{A note dated June 9, 1948, says regarding site of Tantura massacre: “To the region commander. Yesterday I checked the mass grave in Tantura cemetery. Found everything in order.” (IDF Archives)}

The attack on Tantura was not a spontaneous military action but part of a calculated strategy. The village had been specifically targeted under Plan Dalet, the Haganah's master plan for establishing Israeli control over the largest possible area of Palestine. According to the official history of the Haganah, "Sefer Toldot Haganah," the Alexandroni Brigade was explicitly tasked with the "occupation of al-Tantura and al-Furaydis" along with twenty other villages in what was designated as "enemy territory" - land that had been assigned to the Arab state under the UN General Assembly partition plan. Plan Dalet was implemented in early April 1948, six weeks before the end of the British Mandate and the entry of Arab regular armies. The specific assignment to capture Tantura fell to the Alexandroni Brigade's 33rd Battalion.

{Forensic Architecture analysed aerial photos from the British mandate era.}

The testimonies of survivors provide harrowing details of the attack and its aftermath. Muhammad Abu Hana, who was twelve years old at the time, recalled being awakened by heavy gunfire in the middle of the night. Women began screaming and running out of their houses with their children. He witnessed his wounded uncle being discovered by Israeli soldiers despite attempts to hide him. By morning, the shooting had stopped, and the villagers were rounded up on the beach, with women and children separated from the men. The men were searched and ordered to keep their hands above their heads, while female soldiers searched the women and confiscated their jewelry. Abu Hana observed groups of men being led away from the beach, followed by the sound of gunfire after each departure. He later saw bodies piled on a cart, which emptied its cargo into a large pit.

Muhammad Ibrahim Abu 'Amr, another survivor, counted the bodies of seven young people from the village near the house of Badran on the street leading to the mosque. He witnessed a woman named 'Izzat Ibrahim al-Hindi being shot dead after she screamed at the horror of the sight. When the survivors were loaded onto trucks, they saw bodies "piled along the road like stacked wood." A woman recognized her nephew among the dead and later learned that her three sons had also been killed, though she refused to believe it until her death, always insisting they had escaped to Egypt and would return.

Amina al-Masri described how the villagers had feared an attack since the capture of nearby Kafr Lam following the fall of Haifa. On the night of the assault, men were on guard duty at various entrances to the village but were poorly armed. She recalled hearing gunfire and explosions coming from multiple directions. She witnessed Fadl Abu Hana being killed at a place known as the Marah, despite being unarmed and wearing only a khaki jacket. She saw a group of men being taken away and shot, with one survivor deliberately spared and told, "Go tell the others what you saw." In Furaydis, she witnessed a military vehicle driven by a female soldier deliberately run down a woman of Tantura who had been returning from the field with wheat to feed her children.

Farid Taha Salam described the village's limited defensive preparations, noting that they had only a few rifles, one automatic weapon (a Brenn), and some hunting guns. The guard posts were established at several locations, but there were more men than guns available. The guards were poorly trained, with those who had served in the English police being considered the most skilled. When the attack began, the defenders returned fire until their ammunition ran out, with much of it wasted due to inexperience. Some defenders fell back toward the center of the village, others managed to escape Tantura altogether, while a third group remained at their posts until they were killed or captured and executed.

Salam recounted how groups of men were led away one by one after the population had been rounded up. Taha Mahmud al-Qasim, who survived one such group, reported that a Jewish soldier had asked, "Who here speaks Hebrew?" When Taha identified himself, the soldier told him, "Watch how these men die and then go tell the others," before lining up the remaining men against a wall and shooting them. Later, the mukhtar of Zichron Yaacov arrived at the beach where the villagers were being held, but his intervention appeared to have limited impact on the overall situation.

The aftermath of the massacre saw the women and children taken to the nearby village of Furaydis, which had already fallen but whose inhabitants had not been expelled. The surviving men were held in prison camps and eventually transported out of Israel under prisoner exchanges, with their families following later. Most of the survivors ended up in refugee camps in Syria or in the al-Qabun quarter of Damascus. In June 1948, just weeks after Tantura's fall, the kibbutz of Nachsholim was established on its lands by Holocaust survivors. The village itself was razed, except for a shrine, a fortress, and a few houses.

Today, the site of the village is an Israeli recreational area with swimming facilities, and the fortress houses a museum.

The testimonies also reveal the experiences of survivors in the prison camps. 'Adil Muhammad al-'Ammuri described being taken to a camp at Umm Khalid and later transferred to the Jalil prison camp, where prisoners were forced to harvest Arab fields for a Jewish army contractor. He witnessed soldiers opening fire on a group of thirsty men from Lydda and Ramla who were pushing and shoving to reach a water tank, resulting in numerous deaths. Mahmud Nimr 'Abd al-Mu'ti recounted being forced to dig graves for the dead and witnessing the psychological trauma inflicted on survivors, such as sixteen-year-old Taha Muhammad Abu Safiyya, whose hair had turned white after his experience.

Several survivors described escape attempts from the camps. Yusuf Salam managed to flee despite three rows of barbed wire surrounding the camp, suffering cuts to his face and chest in the process. Others reported witnessing tensions between different Israeli factions, with one incident involving the Irgun attempting to enter a camp to "liquidate all the Arab prisoners," only to be confronted by Haganah guards.

{The likely sites of executions and mass graves as well as the boundaries of previously existing cemeteries.}

The Tantura massacre represents a significant but long-overlooked chapter in the history of the 1948 war and the establishment of Israel. Through the testimonies of survivors and the research of scholars like Teddy Katz and Ilan Pappé, a clearer picture has emerged of the systematic violence employed against Palestinian civilians during this period. The events at Tantura stand as a powerful reminder of the human cost of conflict and the importance of acknowledging historical truths, however painful they may be, as a necessary step toward reconciliation and justice.

Sources:

1-https://www.palestine-studies.org/en/node/41048

2-https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20230612-tantura-represents-a-microcosm-to-the-whole-story-of-palestine-palestinian-filmmaker/

3-https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/may/25/study-1948-israeli-massacre-tantura-palestinian-village-mass-graves-car-park

4-https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/israel-middle-east/articles/tantura

5-https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/executions-and-mass-graves-in-tantura-23-may-1948

The core question that should have been asked regarding the Tantura massacre, the Nekba and now the G of the Palestinian people- is- WHO are these genociders?

WHO -WHO are they? We know Britain barred them entry into UK just before 1st WW and after WW2. Why?

Until we understand- fully understand WHO these ppl are, we will fail to understand why they are serving as a colonial outpost, as a convenient trigger, as a monster ecstatically licking its lips.

Excellent film. Good call linking to Forensic Architecture's evaluation!